Rivalries big and small exist everywhere you look. The Red Sox vs. Yankees, Batman vs. Superman, thin crust vs deep dish. The winemaking world is no different, and today we’re going to look at one of the larger debates – whole cluster vs destemming during fermentation.

Winemakers are a fickle bunch, and they subscribe to all sorts of beliefs about how to make great wine. Some swear by the amazing results they get with whole cluster fermentation and others only use the most perfectly hand-sorted, destemmed grapes. With harvest in full swing here in Napa we wanted to look at the differences between these two approaches.

Cabernet Sauvignon grapes getting spun out of a destemming machine

Why use whole clusters?

As you might imagine, whole cluster fermentation involves fermenting grapes along with their stems. Sometimes the grapes are left on the stem, and sometimes they’re destemmed first, then mixed back together. Those green stems can dramatically affect a wine’s flavor, texture, and ageability.

The most obvious effect of stems can be tasted. Whole cluster wines tend to show more vegetal flavors of bell pepper, asparagus, green peas, or earth. Without getting too geeky, these green flavors come from a group of compounds called pyrazines, found in varying levels in all grapes.

At this point you might be asking yourself, why on earth would someone want to make wine taste like pea soup? It’s true, some people treat these vegetal flavors as faults in wine. Robert Parker and James Suckling seem to score wines lower if they show too much herbaceous verve.

Subtlety is key, and it’s quite rare to see a wine made from 100% whole clusters. Even winemakers who love whole clusters recognize the fine line between adding a layer of complexity and smothering it with a heavy layer of steamed asparagus. Most winemakers use a smaller percentage, 30-40% for example, and blend with a batch of destemmed juice to round things out.

Commonly used varietals

Bordeaux varietals like Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Sauvignon Blanc and Malbec have higher amounts of naturally occurring pyrazines. Most Bordeaux winemakers scoff at the idea of using whole clusters. For the most part you’ll find Pinot Noir and Syrah used for whole cluster fermentation. This is especially true in Burgundy and Rhone.

Why? Pinot lacks the tannin that some other grapes have and as a result it might not have the broader mouthfeel. Syrah has an inherent gamey/meaty flavor to it that seems to compliment the savory notes that whole clusters bring to the table. Completely destemmed, these grapes might produce a fairly one dimensional wine, but with whole clusters added to the mix they can rise from average to exceptional.

Producers who like whole cluster ferms

Some of the biggest names in Burgundy, Rhone, and California favor whole cluster ferms. Jeremy Seysses at Domaine Dujac is well known for his love of stems, often using 65-100% depending on the cuvee. He reasons it adds a spicy/sappy layer to their Burgundy. “We have the feeling that we get greater complexity and silkier tannins with whole cluster fermentation” he told writer Jamie Goode in a Wine Anorak piece on the subject.

“We have the feeling that we get greater complexity and silkier tannins with whole cluster fermentation”

Chateau Rayas in Chateauneuf-du-Pape credits whole clusters as partly responsible for creating the haunting aromatics and superb structure that makes their wine age so well. Flowers’ first ever Camp Meeting Ridge Pinot used 100% whole clusters and to this day they remain strong advocates of the method, pointing out how well those early vintages aged.

In California you’ll find producers like Littorai, Laetitia, Failla, Tantara and Au Bon Climat using fairly high percentages of whole clusters in their Pinot Noir. The same goes for many of the Oregon and Washington wineries. Even in Bordeaux some producers like Smith Haut Lafitte have shifted toward using a small percentage of whole clusters to experiment with their final blends.

Beyond flavor

Philip Bascaules, the ex-winemaker of Chateau Margaux told Decanter “technical perfection (total absence of stems) can in fact lower the quality.” The general consensus seems to be that whole cluster wines might be a bit awkward and even slightly offensive in their youth, but they develop more depth and complexity with time.

“technical perfection (total absence of stems) can in fact lower the quality.”

Winemakers are still learning about and experimenting with whole cluster ferms and there’s a good deal of spiritual feeling guiding their efforts. Most agree that certain vineyard sites produce fruit that’s much better suited for whole clusters. They might chew on a stem or grind it into smaller bits to look at the sap in determining whether or not to include stems. This makes sense given the myriad of factors that play into the matrix of winemaking decisions and results. But the following effects seem to be widely accepted:

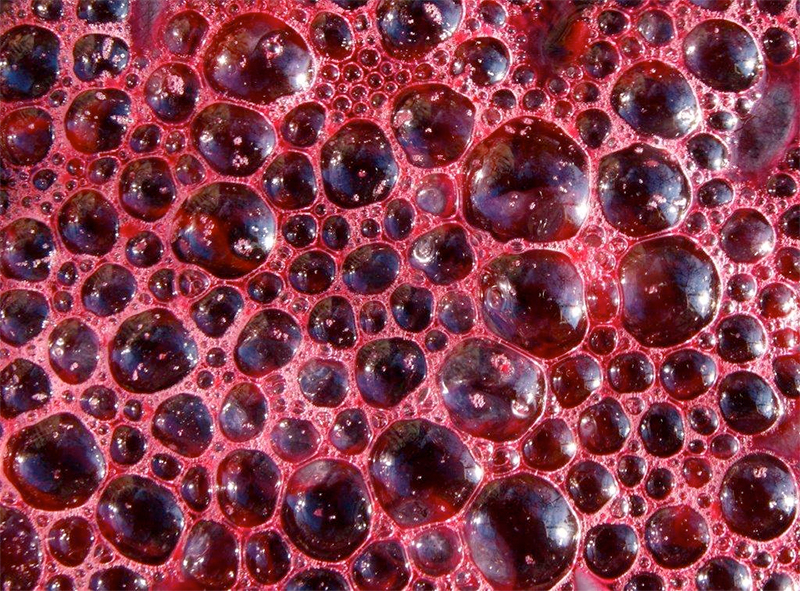

- Heightened aromatics as a result of some berries not breaking, instead fermenting inside themselves. When they do a final press of the juice those grapes might be have a small amount of sugar remaining which prolongs fermentation, adding a subtle layer of complexity.

- Intracellular fermentation (grapes fermenting without being crushed) also prevents the more aggressive seed tannins from being released. This helps create a smoother mouthfeel.

- Tannins from stems might help preserve color and freshness. Stems lengthen the tannin chains and make them more savory than sweet, also helping create a softer feel in the midpalate.

- Temperature is more regulated as juice can freely move around the grapes. This is important because lower temps gently extract tannins and color, resulting in more perfumed aromatics/brighter color.

- Stems absorb color during fermentation, another factor that might contributed to a brighter looking wine.

- Pockets of CO2 get trapped in the stems, which protects wine as it ages in the barrel, requiring less sulfur down the road.

The general consensus seems to agree that a small amount of stems can go a long way in creating aromatic, bright, complex, and age-worthy wines. And everyone agrees that too much can be a very bad thing. Back in the day, fermenting with stems was the norm, simply because they didn’t have the sorting machines they have around today. As winemaking trends shifted and destemming became the new reality, they realized maybe something was missing and today we’re seeing a resurgence in appreciation for stems as winemakers try to find balance on both ends.