Wine prices are often mystified. Very few wineries, wine shops and retailers are willing to openly discuss their margins.

One who isn’t? Coffaro wines.

The true cost of a bottle of wine

David Coffaro is not your typical winemaker, and he’s not afraid to lay out a transparent view of certain topics others do their best to avoid. In an article titled “My $100 bottle of wine” aka The People Deserve To Know the Truth, author Brendan Eliason spells out a brutally honest, detailed, and somewhat cheeky breakdown of what it costs to make a single bottle of wine.

“What can you possibly do to make a bottle cost $100? Were the grapes individually crushed between the thighs of Cuban virgins? Were many overpaid psychologists hired to deal with the wines’ post crush stress? How can $50, $70, $100 or more a bottle ever seem reasonable?”

While his outline is slightly exaggerated for effect, the truth remains clear – the cost to make a bottle of wine is a fraction of what you pay, and prices often relate more to prestige and scarcity than the bottom line cost of goods.

Still this begs the question, how does a $25 bottle end up at $100?

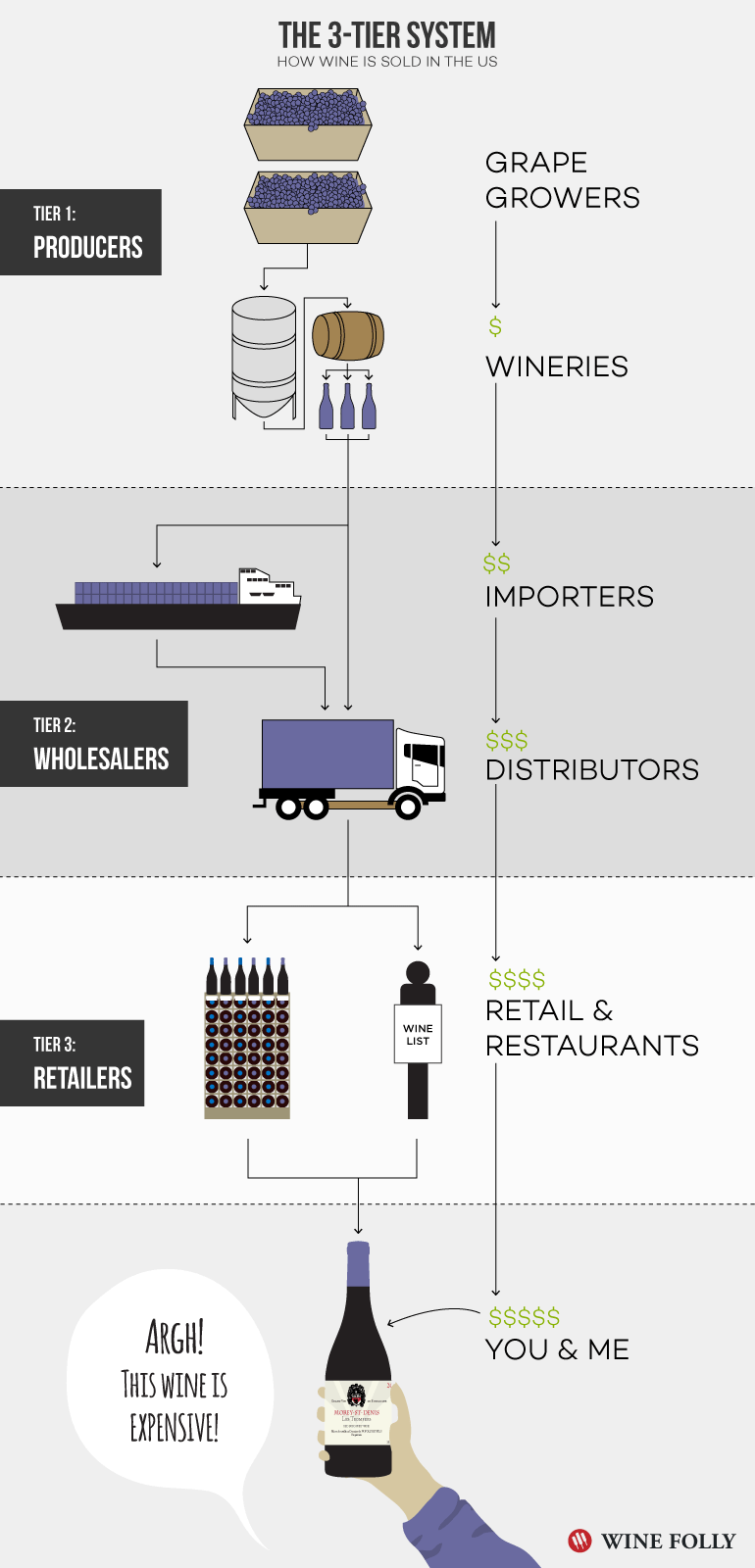

This archaic system exists to limit your choice – and raise prices

Suppose a winery sells their $25/bottle Cabernet to a wholesaler/distributor for $45/bottle. That’s a modest markup. Fair enough considering they need to eat too.

But what happens next is where prices really start soaring upward.

“Even with all this spending I’m only up to $28.25 – a far cry from my $100 goal. Luckily I still have an ace up my sleeve: the three tier marketing system in which I have other people selling my wine.”

The distributor charges the retailer $65, earning a standard 33% margin, and finally the retailer tacks on the de facto 50% margin. Presto! The wine is now listed at $95 on the store shelf. Of course, the MSRP is $100 so you’re really saving 5%!

Via Wine Folly

This process is called the three-tier system. It’s not completely evil. It does, after all, keep a variety of wines on store shelves. It also means the consumer pays several middle men a hefty markup, and while the winery might add a marginal price bump, the increases from distributors and retailers are by percentage — and that means prices compound drastically at each stage.

While most states have opened their doors to out of state shipments from wineries, many still ban online retailers from sending wine across their state lines. So if your local shop sells out of Opus One or Shafer, and you want to order from a website, you might be out of luck. Imagine if you had to buy Nike sneakers from the local Foot Locker instead of Zappos. Or razors from CVS instead of Dollar Shave Club.

Cheap bulk juice by any other name is still just cheap bulk juice

Here’s another tricky thing you’ve no doubt seen.

Exceptional deal, or marketing gimmick?

A new wine club pops up, promising to cut out the middleman by shipping direct to consumer. They have really whimsical names and even teamed up with the coolest street artist from Brooklyn to design a really hip label.

These wines may not be terrible, but nobody’s ever heard of them. They probably haven’t been scored by critics (whether that matters or not is a whole other topic). And unlike wines coming from a negociant, who might have close relationships and contracts in place to buy juice from certain growers/vineyards every year, with bulk juice the quality can change drastically between years.

“If you’re drinking a bulked-off white label wine that cost the manufacturer $1.50 to produce and it’s $13 cost to you, is that really a better “value” than a hand-made, farming focused wine that cost $3 a bottle to produce that’s $15 on the shelf?”

– Madeline Puckette, The Trouble With White Label Wines

Here’s the deal: you can buy bulk red blend from Paso Robles for $9/gallon. That’s $1.80 worth of juice per bottle. Stainless steel aging takes keeps oak out of the equation, and with the cork (30 cents), glass (50 cents), label (33 cents) and bottling you’re spending another couple dollars. Let’s be generous and say it cost $3.50. At a retail price of $13.99 it brings a 400% markup and a very handsome margin.

So when you ask yourself, “How does Last Bottle get such stupendous deals on great wines?” you have your answer – we scour everywhere – from Napa to Tuscany – in search of incredible wines, buy direct from the families who make them, and then remove the middle men from the equation.

The end result? You get a legitimately great wine for a fair price.