If you think mead is sooo 476 AD, then it’s time to think again. The drink of the gods is on the up and up in the 21st century, and not just at Renaissance fair either– mead is moving beyond home brewing and into the mainstream beverage market.

According to Fortune Business Insights, the mead market brought in 432 million USD in 2020, and is projected to amass 1.6 billion dollars by the year 2028. That projected rise of 18% in the world beverage market should not be overlooked. Remember the days when your local brewery didn’t have kombucha on the menu? We do too, but man, these seemingly fringe bevs hit the mainstream fast! Honey wine is up next to bat, and we’re expecting a home run for history’s fabled elixir.

Why? Because it’s pretty damn good.

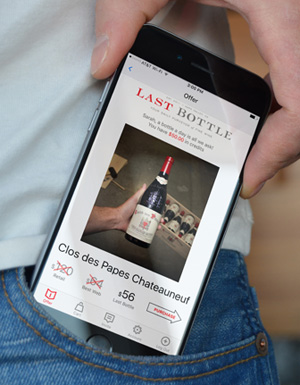

Though it’s early in its 21st-century claim to fame, we think it’s high time that wine lovers give mead an honest try. So, wine lovers, down your tureens of highly quaffable, ultra delectable, discounted wine (wink, wink) and fill it with one of humanity’s great marvels – honey wine.

What is Mead?

Mead is an alcoholic beverage made from fermented honey. It is the oldest alcoholic bevvy known to mankind, enjoyed by civilizations around the globe for thousands of years. Ancient Greeks knew it as the drink of the gods, Celts believed it to possess magical powers, Vikings guzzled it in celebration, the list goes on…

The ancient elixir is commonly referred to as honey wine, but mead is not wine, and it’s not beer either. In order to fully understand mead, we have to acknowledge that it is a different beast entirely. But that’s not to say that mead should not be appreciated with the same regard that wine is, especially the mead that is popping up in craft beer and artisan wine shops today.

Don’t let the honey fool you, it is way more than a syrupy-sweet, home brewer’s delight. Mead can be complex, nuanced, and range from sweet to bone-dry. Its profile varies widely, depending on the honey varietal it was made from and the region the bees made it in. What we’re getting at here is that modern meaderies are establishing that honey wine can be just as serious as wine, and is worth a revisiting from even the most discerning wino.

How Mead is Made

It starts with flowers. Flowers produce pollen and nectar that bring the bees, who transform flower nectar into honey. Raw honey is harvested by beekeepers, and transferred to the meadery where it is mixed with yeast and water. These three ingredients are all that’s required, but flavoring agents such as fruit, hops, or spices can be added at this stage. Once mixed, the liquid is transferred to a stainless steel tank for its primary fermentation. Mead’s primary fermentation is similar to wine’s primary fermentation, except that the honey contains all of the sugars that a wine would contain from the grape must. The yeasts will consume the sugars for one to three weeks, producing alcohol ranging from 7 to 14 percent ABV for standard meads and 14 to 20 percent for sack meads.

Once the primary fermentation is complete, the base wine will be racked off into another tank for it to settle. In this second stage, the mead is put to rest so the yeast sediment can separate from the must. The mead will settle and separate from the lees for two to four weeks, sometimes more. From there, some meaderies will choose to incorporate fruit juice or wine to make melomel or pyment, respectively.

Then the mead is bottled and oftentimes aged in the bottle for months. The higher the ABV, the more aging the mead needs. Much like wine, aging is crucial to bring out nuances and to resolve intense primary flavor notes and achieve a more cohesive integration in the mead.

Styles of Mead

Mead has a wide variety of styles; these styles are determined by the brewing process, and can vary widely depending on the type of honey used and the region it was made.

Show Mead (Traditional Mead)

This is as plain and simple as mead can get: just a mixture of honey, yeast, and water with an alcohol content between 7 and 14 percent.

Sack Mead

Just like traditional mead, but with a higher alcohol content. Sack mead has an ABV ranging from 14 to 20 percent.

Melomel

Melomel is fruit mead, whether that be berries, stone fruits, raisins, or citrus. Melomel made with apples is sometimes called cyser, and melomel made with grapes is called pyment.

Metheglin

Mead made with spices or vegetables, the most common of which include cinnamon, clove, and anise.

Braggot

Mead made with hops and grains.

Bochet

Mead made with caramelized honey.

A Note on Honey

There are over 300 unique honey types out there, and the type of honey used in the base of your mead makes a major impact. Think of the honey like you’d think of the grape varietal– it is the basis of the drink.

You may be thinking, how are there only 300 honey varieties out there, shouldn’t there be an unquantifiable amount? And if you were thinking that, you would be right. Every hive will make their own honey variety based on the terroir it’s in, but we categorize honey based on human consumption, not the bees’ mastery of the craft. There are 300 distinct ways in which beekeepers have intervened to make a distinct varietal. Manuka, acacia, buckwheat, alfalfa, sage, and dandelion honey are all monofloral honeys made by strategically placing hives– a human intervention. If there is no specific floral intervention by a beekeeper or farmer, the honey will be considered polyfloral, made from the nectar of the local flora. If that honey was made within 50 KM of you, it is local honey. A local honey may be vastly different from another made from a hive just 50 km away; just as a Napa cabernet sauvignon may be vastly different from a Sonoma cabernet sauvignon.

Most honey varieties are named after the flowers the bees pollinated and collected nectar from. If your Honeybear says its contents are clover honey, that’s because the bees that made it collected nectar from clover flowers. Beekeepers achieve this by positioning their hives at an advantageous spot for nectar collection; if the goal is for the bees to make clover honey, the bee hive will be positioned smack-dab in a clover field. But it is important to note that beekeepers cannot be 100 percent certain that the nectar their bees collect is exclusively from the flower on the label, because even domesticated bees travel up to five miles from their hives to collect honey. Most honey varieties are made from a majority of the nectar on the label, mixed with the flowering species surrounding the hive. (That’s what makes local honey so magical for those who suffer from seasonal allergies. Your local bees are effectively microdosing you with the allergens in your area.)

One of the most common honeys used in craft mead is orange blossom honey, for its citrusy flavors. The resulting wine is typically crisp and lively, and can present tasting notes that range from pickled orange peel, clove, mango and pineapple. Clover honey is another ever-present variety in mead, offering a delicate and clean palate, ideal for melomel.

The most common honey variety for mead, however, is the illusive local honey. Local honey is simply honey made from the nectar of a region’s local flowers. Most meaderies craft mead with honey made in their own backyards, so the resulting beverage can express the terroir in which it was created. This is where mead initially peaked my interest as a wine lover. Drinking mead is not just drinking honey, it’s drinking flowers. Every sip of mead reflects the vintage it was harvested, the will of the hive, and the nature that surrounds it.

History of Mead

Mead’s origins can be traced back to the dawn of agriculture, when humans transitioned from nomadic hunter-gatherer societies to settled communities, around 7000 – 3000 BCE. Early evidence of honey wine production dates back to ancient China, India, and Europe, where fermented honey and water mixtures were discovered in clay pots. The origins of mead correlate directly to the origins of pottery, and like most alcohols, is believed to be created by accident. When honey has a pot to sit in, fermented godly-nectar is a happy accident waiting to happen.

Mead-making continued to evolve in the hands of Ancient Egyptian and Greek civilization, around 3000 to 500 BCE. The Egyptians used honey wine as an offering to the gods and consumed it in religious rituals. Meanwhile, the Greeks considered mead to be ambrosia, the preferred drink of the godson Mount Olympus, further solidifying its divine reputation.

Mead played a significant role in Norse mythology and culture, and this Norse influence is a hallmark of mead’s history. (Thanks, Beowulf!) The Vikings crafted mead and often enhanced its flavor with herbs and spices. It became a central element of their feasts and celebrations, and the term “mead-hall” was used to describe the grand halls where such gatherings took place. In Norse mythology, the Poetic Edda mentions a special mead, the “Mead of Poetry,” which grants the gift of poetic inspiration.

Mead’s popularity spread across Europe during the Bronze Age, between 2800 to 1800 BCE, with various regions developing their own unique recipes and traditions. Monasteries became centers of honey wine production, refining the art and techniques of brewing, but as the centuries passed, mead’s popularity waned in favor of beer and wine. This shift was not rooted in the taste of the times, but in necessity. Making mead means harvesting honey, and dealing with bees – it’s a lot of work to get those raw materials compared to the fields of wheat and vineyards of grapes used to make beer and wine. Throughout the middle ages, fermented drinks became a necessity due to poor drinking water conditions, and beer became the go-to because it is easier to make than delicacies like mead. And as sugar became readily available through trade routes in the 11th century, harvesting honey made less and less sense. The production of honey wine became less common throughout the centuries due to these logistical factors, but it was still associated with rural and folk traditions. Honey wine trudged on in those folk traditions for centuries, but had completely gone out of fashion in the 1700s. By then, mead held less cultural significance, the people’s tastes had gravitated toward spirits, which were starting to emerge at the time. But today, the mead resurgence is upon us.

Mead in Modern Times

It’s impossible to talk about mead without discussing homebrewing. Because mead is so fringe, especially here in the US throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, it’s no wonder that a homebrewing culture would emerge. Honey wine home brewers make up the basis of mead consumers today, and have been shaping the US’s mead culture for years.

The mead homebrewers are a cool community of fermentation geeks who overlap largely with the beer home brewing community. The Homebrewers Association found that there are over 1.1 million home brewers in the US. Most DIY mead-makers found mead through their homebrewing journey; honey wine is often poised as an easier first step to making beer or wine or as a fun alternative to hops and grapes.

Those home-brewers have ignited the mead renaissance, and some of them have gone on to create the meaderies that are solidifying mead’s place in today’s premium beverage scene.

In the year 2020, about 500 craft mead manufacturers were operating in the US. These meaderies exist across the country, with at least one meadery in all 50 states. The undeniable mead hub here in the US, however, is none other than Michigan, clocking in with 24 meaderies. This can be attributed to the fact that Michigan is only second to California in crop variety, and is home to a large beekeeping community. The Mitten State takes to mead like bees to honey.

Serving Mead

Generally, lighter meads, such as traditional or melomel meads, as well as sparkling meads, are best served slightly chilled, between 45 to 55 degrees fahrenheit. This temperature range allows the subtle flavors and aromas to shine without being overwhelmed by excessive coldness. For heavier meads like pyments, barrel aged meads, or meads with higher alcohol content, serving them at a slightly warmer temperature, around 60 to 65 degrees fahrenheit, can bring out their complexities. It’s similar to wine tasting, where whites and light bodied reds are ideally served with a slight chill, and bigger, higher alcohol, more concentrated reds like cabernet and Bordeaux need to be served at warmer temps for optimal enjoyment.

For stemware, choose for mead like you would choose for wine. Sparkling meads do well in tulip glasses, lighter meads in standard wine glasses, and rich, heavy meads in a port glass. The wine-glass shape helps concentrate the aromas, allowing you to fully appreciate the mead’s bouquet.

Pairing most standard meads can be very similar to pairing white wines. Therefore, fish, chicken, and vegetable dishes will always be a safe bet. Honey wine also pairs nicely with spicy asian and Indian cuisine. Sweeter, darker meads, however, are best when paired like you would a fortified wine. Dark meads are paired nicely with creamy cheeses, nuts, dark chocolate, and desserts.

Why Mead?

Just like wine, mead is an experience that encapsulates the beauty of nature. It’s no longer just the drink of Rennfairs – it’s in a renaissance of its own. Mead is one of the world’s most versatile and historied alcoholic beverages; just one sip can convert you. In between your sips of glorious, ultra discounted vino (ahem, see what we’re drinking today), give history’s favorite drink a try.