With the forecast predicting 90+ degrees here in Napa tomorrow it can only mean one thing – #RoséAllDay baby! The Rise of Rosé is undeniable. Just five years ago your local BevMo had maybe ten bottles, and today they stock 50+. Yes, pink juice has become undeniably hip, and today we have more options to choose from than ever.

Just about any red grape is used to make rosé, and it largely depends on the region. In Provence they use mostly Grenache, Cinsault, Mourvedre, Syrah, Sangiovese, and Carignan. In Napa they might use Cabernet, while in Rioja it’s Tempranillo. Each varietal lends its own subtle personality to the finished wine, but regardless of the grape, most rosés probably share a few common elements – bracing acidity, low alcohol, a lack of oak aging, and fresh berry flavors.

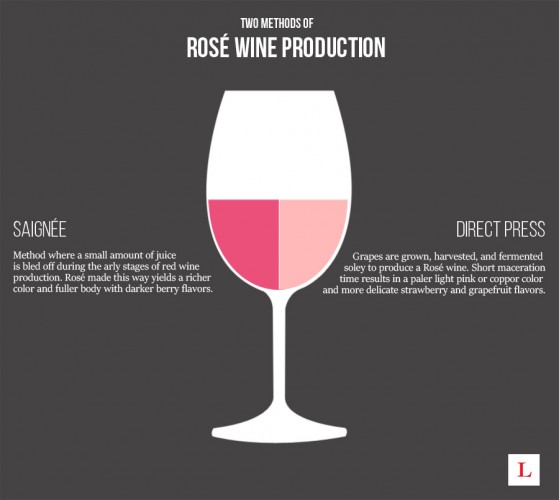

In fact the most compelling differences between two bottles probably doesn’t depend on the varietal but rather the production method – either saignée or direct press maceration. Before you decide to say #yeswayrose there are a few things you should know about these two methods.

You say saignée, I say no way

Rosé production is split between two primary methods, each yielding a slightly different style. The direct press method is preferred by purists in the southern France regions of Provence and Languedoc-Roussillon, while the saignée method is more common in places where they make higher end red wines.

Saignée Method

From the French word for “bleeding”, the saignée method is a by-product of making red wine where a small amount of juice is bled off early in fermentation. This helps increase concentration of the remaining juice in the same way you’d reduce a sauce to intensify flavors. Once the juice is separated, the winemaker has a few options. They can simply pour it down the drain, use it to top off barrels of wine (ullage) – or make a rosé.

Rosé made this way tends to have deeper, more vibrant pink color and darker flavors of blackberry, raspberry, and berry jam. While some think of this technique as an afterthought of red wine production, supporters of the saignée method insist their wines are purposeful, and argue it produces the riper flavors and greater expression of the varietal.

Direct Press (Maceration) Method

Many producers, especially those in Provence and Languedoc-Roussillon, take a more traditional approach to making rosé. Grapes are grown and selected exclusively for rosé production, often crushed as whole clusters, and then gently pressed until the juice reaches a desirable pale color. Some producers may also allow a few hours skin contact (maceration) before separating the juice from the must, which adds a richer color to the finished product.

Winemakers who use this method praise its more deliberate approach which starts during harvest when grapes are picked at lower brix to keep the alcohol levels down while bringing up the acidity. Saignée might yield more robust flavor and deeper pink color, but the direct press method ushers in more perfumed aromatics and delicate flavor compounds like strawberry, bright cerry, and rhubarb.

Which Rosé is better?

You might come across articles saying saignée makes the “best quality rosé”. But is that really true? François Millo, president of the Provence Wine Council doesn’t think so. He had some harsh words about the saignee method, telling The Drinks Business it’s a “bad way to make rose”.

“People who make saignée rosé are opportunists. In their mind they are making red wine – the rosé just happens to be a by-product.”

François Millo

Of course there’s plenty of great saignée rosé out there. Despite strong feelings on both sides, it’s hard to say which method is better. Ask a dozen winemakers and you’ll get all sorts of responses. It really boils down to your preferences. Like higher acidity and strawberry/rhubarb flavors? Stick with a Provencal rosé. Want a bigger style? Try a saignée from Napa. At the end of the day, what really matters is whether or not you’d open a second bottle.